"Word of God" is not infrequently simply wrong

"When we portray the God of the Bible as hating everyone that the chosen people hate, is God well served? Will our modern consciousness allow us to view with favor a God who could manipulate the weather in order to send the great flood that drowned all human lives save for Noah's family because human life had become so evil God needed to destroy it? Can we imagine human parents relating to their wayward offspring in this manner? Can we really worship the God found in the Bible who sent the angel of death across the land of Egypt to murder the firstborn males in every Egyptian household in order to facilitate the release of the chosen people? Can the Bible still be of God when it portrays Joshua as stopping the sun in the sky for the sole purpose of allowing him the time to slaughter more of his enemies, the Amorites (Josh. 10:12-15)? Can the Bible be the "Word of God" when it has Samuel order King Saul in the name of God to "Go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have; do not spare them, but kill both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass" (1 Sam. 15:3)? Is it the "Word of God" when the Psalmist writes about the Babylonians who have conquered Judah: "Happy shall he be who requites you with what you have done to us! Happy shall he be who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rocks" (Ps. 137:8-9)? These are but a few of the questions I want the Bible quoters to answer. Is Christianity somehow irrevocably linked to this mentality because of our continuing claims for the Bible?"

Historically the evidence is clear that the verb "to be" has been employed in church circles for centuries to give authority to the Bible. Nor is there any doubt that these claims for the Bible have also shaped traditional Christianity for its entire history. I now, however, want to open this debate to new possibilities by asking a few simple but very direct questions: Was this claim for the Bible to be the "Word of God," no matter how it is interpreted, ever appropriate for this volume which contains sixty-six books (or even more if you count the Apocrypha) that were written over a period of perhaps twelve hundred years? Can such a claim stand even the barest scrutiny? Is Christianity so shaped by this strange claim as to be unable to extricate itself from its biblical moorings and still be recognizable? Is this claim not the primary source from which evil has flowed so freely from the Christian church throughout Christian history? Has not this definition been the very thing that has produced the religious mentality that has perfumed prejudice, violated people literally by the millions and created an idol out of the scriptures that even in our somewhat enlightened generation is still allowed in some circles to masquerade as if it were the final inerrant authority? It is quite clear to me that it is the assumption that the Bible is in any sense the "Word of God" that has given rise to what I have called in the title of this book "the sins of scripture." By "the sins of scripture" I mean those terrible texts that have been quoted throughout Christian history to justify behavior that is today universally recognized as evil.

To face this reality is essential for my integrity as a Christian, but it is not easy. My religious critics say to me that there can be no Christianity apart from the authority of the scriptures. They hear my attack on this way of viewing the Bible as an attack on Christianity itself. I want to say in response that the claim that the scriptures are either divinely inspired or are the "Word of God" in any literal sense has been so destructive that I no longer want to be part of that kind of Christianity! I do not understand how anyone can saddle God with the assumptions that are made by the biblical authors, warped as they are both by their lack of knowledge and by the tribal and sexist prejudices of that ancient time. Do we honor God when we assume that the primitive consciousness found on the pages of scripture, even when it is attributed to God, is somehow righteous? Do we really want to worship a God who plays favorites, who chooses one people to be God's people to the neglect of all the others?

When we portray the God of the Bible as hating everyone that the chosen people hate, is God well served? Will our modern consciousness allow us to view with favor a God who could manipulate the weather in order to send the great flood that drowned all human lives save for Noah's family because human life had become so evil God needed to destroy it? Can we imagine human parents relating to their wayward offspring in this manner? Can we really worship the God found in the Bible who sent the angel of death across the land of Egypt to murder the firstborn males in every Egyptian household in order to facilitate the release of the chosen people? Can the Bible still be of God when it portrays Joshua as stopping the sun in the sky for the sole purpose of allowing him the time to slaughter more of his enemies, the Amorites (Josh. 10:12-15)? Can the Bible be the "Word of God" when it has Samuel order King Saul in the name of God to "Go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have; do not spare them, but kill both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass" (1 Sam. 15:3)? Is it the "Word of God" when the Psalmist writes about the Babylonians who have conquered Judah: "Happy shall he be who requites you with what you have done to us! Happy shall he be who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rocks" (Ps. 137:8-9)? These are but a few of the questions I want the Bible quoters to answer. Is Christianity somehow irrevocably linked to this mentality because of our continuing claims for the Bible?

One can easily descend from these serious questions to those that are a bit more frothy, frivolous and fun. Many of these biblical assertions have floated across the Internet in a variety of versions, making good reading for a biblically illiterate nation. According to the Bible, one of these Internet offerings noted, it is permissible to sell one's daughter into slavery (Exod. 21:7). It is of interest that sons as candidates for slavery are never mentioned. One may possess slaves, says the Bible, but only if they come from neighboring countries (Lev. 25:44). One wonders, as an American, if that makes both Canadians and Mexicans eligible!

The execution squads would have to work overtime to keep up with the number of texts from the Bible that call for the death penalty. Violating the Sabbath (Exod. 35:2), cursing (Lev. 24:13-14) and blaspheming (Lev. 24:16) are among them. Such judgments would fall most heavily on athletic locker rooms used in preparation for Saturday or Sunday football games! But of course no one should be playing football anyway, for Leviticus also prohibits touching anything made of pigskin (Lev. 11:7-8)! Perhaps this great American fall sport should be played with rubber gloves! Even stubborn and rebellious children are at risk of capital punishment, according to the Bible. If children do not obey their parents, if they overeat or drink too much, they are to be stoned at the gates of the city (Deut. 21:18-21). That is a bit stricter than even right-wing biblical moralists and ideologues care to go. Yet if one wishes to search the scriptures sufficiently, this rather bizarre list of texts can be expanded almost endlessly.

The case against the Bible, however, does not stop at the end of clever lists. It is quite easy to demonstrate that the Bible is simply wrong in some of its assumptions. It is hard to maintain the claim of inerrancy in the face of biblical statements that are obviously incorrect. The "Word of God" is not infrequently simply wrong.

Moses did not write the Torah: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. Moses had been dead for three hundred years before the first verse of the Torah achieved written form. Those books reflect multiple strands of material that were put together over a period of at least five hundred years. One of those Torah books, Deuteronomy, even provides us with the account of Moses' death and burial (chapter 34). Is it not a rather remarkable author who can record in his writing that particular moment in his own life? Yet Jesus himself makes the traditional claim for Mosaic authorship of the Torah in multiple places in the gospel record (see Mark 1:44; Matt. 8:4, 19:7, 8, 22:24; Luke 5:14, 20:28, 24:27). It is also a working hypothesis in parts of the Old Testament.

David did not write the Psalms. Scholars locate the writings of most of the Psalms during the period of Jewish history called the Babylonian Exile, which started with the fall of Jerusalem in 596 BCE and lasted in some of its forms until the mid-400s. That would be between four and six hundred years after the death of King David. Yet, once again in the gospels, the Davidic authorship of the Psalms is asserted by Jesus (see Mark 12:36-37; Matt. 22:43-45 and Luke 20:42-44). Such a claim made today on a final exam, even at the seminary where I was trained, would result in a failing grade. Jesus, or those who thought they were quoting Jesus, was simply wrong about that.

The case for the Bible possessing the authority of being the "Word of God," or at the very least having been divinely inspired, gets even murkier when the biblical claim is made that epilepsy and mental illness are both caused by demon possession, or that profound deafness, what we once referred to pejoratively as being "deaf and dumb," is caused by the devil tying the tongue of the victim. Can the "Word of God" be bound to levels of knowledge that were transcended centuries ago? Yet once again in a variety of biblical passages Jesus is portrayed as making these specific claims (see Mark 1:23-26, 9:14-18; Matt. 9:13 and Luke 9:38-42).

The fact that we know today that the earth is not the center of the universe, with heaven above the sky, renders the worldview of the biblical writers seriously inaccurate. Was God ill-informed or did God choose not to reveal such truth to the authors of the biblical books? Yet an earth-centered, three-tiered universe underlies such biblical stories as the Tower of Babel (Gen. 11), manna falling from heaven (Exod. 16:4ff.), the wise men following the star of Bethlehem (Matt. 2) and even the cosmic ascension of Jesus (Luke 24; Acts 1).

The Bible tells us that the Israelites wandered nomadically in the wilderness between Egypt and the Promised Land for forty years, guided by the magic signs of a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night, which connected them with the God who lived just above the sky (Exod. 13, 16:35).

The Bible makes assumptions that most of us who live in a post-Newtonian world of "natural law" could never make. Special people in the Bible were said to have had their lives marked by signs of divine favor. Elijah and Elisha, for example, both had miracle stories connected to their lives in the developing traditions. These miracles included the ability to expand the food supply (1 Kings 12:8-16, 17:8-16); the ability to enable an iron axe-head to float on the river (2 Kings 6:5) and even the experience of raising the dead (1 Kings 17:17-24 and 2 Kings 4:8-37). When we come to the Jesus story, a literal reading will reveal either unbelievable miracles or a land of make-believe. Like all great mythical heroes, Jesus was said to have had a supernatural birth. He was conceived without benefit of a male agent (Matt. 1:18-25 and Luke 1:26-38). It was a bit more spectacular than the birth of John the Baptist, who was simply conceived when his father was elderly and his mother was postmenopausal (Luke 1:5-25). Before these two boys were born, we are told, their relative importance was announced when the fetus of John the Baptist, while still in the womb, leaped to salute the fetus of Jesus (Luke 1:41-44). Surely no one would seriously argue that this story was literal history! The birth of Jesus gets more spectacular yet. It is announced to the world by a star that illumined the heavens. The star was said to have had the power to wander through the sky so slowly that it could guide wise men from the East first to the palace of Herod and second to a house in Bethlehem where Jesus could be found (Matt. 2:1-12). Next Luke tells us that on the night of his birth angels split the night sky, behind which they were presumed to live, in order to sing to hillside shepherds. The angels must have sung in Aramaic, for that was the only language the shepherds understood (Luke 2:8-14)!

In a narrative about the child Jesus at age twelve, we are told that he was capable of confounding the greatest teachers of the land (Luke 2:41-52). Stories showing the hero possessing godlike wisdom as a child constitute a familiar theme in the mythology of many great leaders.

We cannot read the rest of the gospel narratives without confronting the image of Jesus as a worker of miracles, from walking on water to stilling the storm. If we believe these stories in any literal way, we have to presume that God suspended the laws of the universe in the first century to allow Jesus to demonstrate his divine origins. The only alternative is to be forced to face the fact that we have in the gospels only mythical accounts of Jesus' life. In either of these rather sterile choices it becomes very difficult to assert that these narratives are the "Word of God."

When we turn to the writings of Paul, the claim that the words of this rather passionate, intensely human and clearly conflicted man were in any sense the "Word of God" borders on the absurd. Since no one would ever confuse Paul with God, there appears little rationality in the attempt to confuse the words of Paul with the "Word of God." Paul was many things, but divine was not one of them.

When Paul says in his letter to the Galatians, "I wish those who unsettle you would mutilate themselves" (5:12), is there something godlike in his words that I am missing? How about his advice to women to keep their heads covered in worship or his assumption that the ancient Hebrew myth of Adam and Eve proved that women were inferior to men (1 Cor. 11:2-16)? When Paul or one of his disciples instructs women to subject themselves to their husbands (Eph. 5:22), slaves to obey their masters (Col. 3:22 and Eph. 6:5) and children to obey their parents (Col. 3:20 and Eph. 6:1-3), surely that is not the eternal "Word of God" speaking. These are the reflections of a rather discredited cultural sexism, an immoral oppression of human life and an obsolete guide to good parenting being revealed here. When the holy God is identified with such bankrupt ideas, surely God is not well served.

In contemporary studies of the way the gospels came into being, scholars are all but unanimous today in asserting that Mark was written first and that both Matthew and Luke incorporated Mark into their narratives. The problem for the excessive claim of a divine origin for the scriptures then comes when we discover that both Matthew and Luke changed Mark, expanded Mark and even omitted portions of Mark. That is not exactly the way one treats something identified as the "Word of God," or even something thought to be inspired by God. The problems grow when these same studies reveal that Matthew and Luke periodically disagreed with Mark and thus contradicted him. Luke went so far as to edit Mark's poor grammar, treating his Marcan source very much as an English professor might treat a freshman's term paper. Mark ended his gospel with the dangling phrase "for they were afraid" (16:8), which Luke simply omitted (24:1-12). Clearly the gospel writers themselves had no concept that either they or their sources were writing the "Word of God." Luke indeed insists that he is writing only after consulting other, presumably conflicting accounts, to compose an "orderly one" (Luke 1:1-4).

The gospel writers are also not averse to ripping biblical stories out of their Hebrew context and using them to buttress their arguments for Jesus as the fulfillment of the prophets. A defensive writer who twists or tweaks his sources so that they will serve his purpose hardly gives evidence of the fact that he is writing something that might be referred to either as the revealed "will of God" or the inspired "Word of God." Matthew is, in my opinion, the writer most guilty of this abuse. He bases his virgin birth story, for example, on Isaiah 7:14. Yet he translates that text to read that a virgin shall conceive (see Matt. 1:23) when the text in Isaiah not only does not use the word "virgin" but says that a young woman is with child. In the world I inhabit, if a young woman is with child, she is hardly a virgin! He also twists either a passage that refers to a holy man as a nazirite (Judg. 13:5), or a passage that uses the word nasir, which is translated "branch" (Isa. 11:1), to suggest that the Hebrew scriptures had centuries earlier referred to Jesus growing up in the village of Nazareth (see Matt. 2:23). That is a rather huge stretch even for a gospel writer!

Later, the church fathers would build the superstructure of the Christian creeds, doctrines and dogmas on the same shaky foundation of assuming that the Bible contained the irrefutable words or "Word of God." So the virgin birth was placed into creeds along with the cosmic ascension, though I know of no reputable biblical scholar in the world today who thinks that either ever happened in any literal way. Nor do scholars today believe that the prophets predicted things that Jesus actually did. That is a gross distortion of scripture. Yet much of the Christology debate in early church history depended on that assumption. Not only was the Jesus story in the gospels written some forty to seventy years after the earthly life of Jesus had come to an end, but it was written quite deliberately with the Hebrew scriptures open so that the story of Jesus could be conformed to those expectations. Various doctrines of the Christian church quake in instability with this undoubted recognition.

The idea that God would plant holy hints of Jesus' life into the writings of Jewish prophets some six to eight hundred years before the birth of Jesus is fanciful enough, but when you then suggest that as these books were being copied anew in each generation-for that is the only way an ancient text could be preserved-God watched over the copiers to make sure that they did it correctly, and that in times of war and natural disaster God guarded these sacred texts from destruction so that when Jesus came people would recognize him as Messiah because he fulfilled these expectations, rationality rebels and proclaims, "There is something wrong in this equation." It violates everything we know about how the universe operates. It defines God as a super manipulator.

When all these things are put together, it becomes clear that the traditional claim that the Bible is in any literal way the "Word of God" is problematic at best and absurd at worst. To the degree that the historical liturgies of the church are themselves dependent on these same biblical claims, it becomes obvious that they too will collapse as soon as these things become consciously evident. The future of the Christian enterprise, therefore, does not look secure, at least to the extent that it is based on the premise of the authority and literal historicity of scripture. The hysterical denial of these obvious biblical truths that mark the life and rhetoric of right-wing churches, both evangelical Protestant and conservative Catholic, is not a sign of hope. It matters not that these churches attract thousands of worshipers who come craving both authority and certainty. This is rather just one more sign of an internal sickness that has not yet been adequately faced by Christian leaders. The constant attack of these right-wing voices on Christian scholarship is a clear tip-off that they cannot face reality. When people cannot deal with the message, the ancient and still regularly practiced tactic is to shoot the messenger.

The greatest tragedy that has arisen because of the way these claims have been made for the Bible, however, is not just the impending collapse of organized religion, as frightening as that now is to many; it is rather in the moral dilemma that comes when religious people face the evil and pain done to so many people over the centuries in the service of these biblical claims. It is high time to call the church and this use of the Bible itself to accountability.

Text by text I will seek to disarm those parts of the biblical story that have been used throughout history to hurt, denigrate, oppress and even kill. I will set about to deconstruct the Bible's horror stories. But destruction is neither my aim nor my goal. I want above all else to offer believers a new doorway into the biblical story, a new way to read and to listen to this ancient narrative. I want to lead people beyond the sins of scripture embedded in its "terrible texts" in order to make a case for the Bible as that ultimate shaper of the essence of our humanity and as a book that calls us to be something we have not yet become. I want to present a different portrait of Jesus, not as a mythical hero, not even as a divine invader of humanity, but as a God presence, a new dimension, even a new vision, of what human life was meant to be.

There is a story told about Elijah in the book of 1 Kings (19:4-18) that guides my efforts. Elijah had been defeated and hounded by his enemies, who thought him responsible for the fact that the popular religion of the people was collapsing. He prayed in his despair for God to take away his life, since in his mind the original covenant had been forsaken, the altars thrown down and the prophets slain. God, instead, invited Elijah to stand upon a mountain and to watch a great and mighty wind rend that mountain into pieces. Then came an earthquake that broke open the great rocks and finally there came a fire of consuming power. God was not in any of these. Yet each of these incredible and fearful acts of destruction had to be endured before Elijah was able to hear "the still small voice." God was in that small voice, and the divine message urged him to return to the work to which he had been called.

I am now convinced that institutional Christianity has become so consumed by its quest for power and authority, most of which is rooted in the excessive claims for the Bible, that the authentic voice of God can no longer be heard within it.

So I want to invite people to a mountaintop where together we can watch the mighty wind, the earthquake and the fire destroy those idols of creed, scripture and church, all of which have been used to hide us from the reality of God.

When that destruction is complete, my hope is that we too will then be ready to hear that still, small voice of calm that bids us to return to that vocation which is, I believe, the essence of what it means to be a disciple of Jesus. We are to build a world in which every person can live more fully, love more wastefully and be all that God intends for each person to be. In that vocation we will oppose everything that diminishes the life of a single human being, whether it is race, ethnicity, tribe, gender, sexual orientation or religion itself. That is what I see Jesus as having done, and because he did exactly that, people were able to see, to meet and to experience God in him in a radically new way.

That is the Jesus I hope to sketch out when the deconstruction is complete, so that my readers will close this book not with the shreds of a destroyed Bible in their hands, but with the vision of a new humanity before them. An ambitious task? Perhaps! But that is the primary task of reformation.

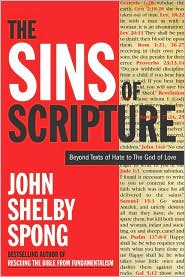

John Shelby Spong, The Sins of Scripture

HarperCollins, 2009, pp. 17-26

Disclaimer: This non-profit site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the education and research provisions of "fair use" in an effort to advance a better comprehension of controversial religious, spiritual and inter-faith issues. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than "fair use" you must request permission from the copyright owner.